Like most investors, I studied a number of different approaches for investing in the stock market. The number of different strategies is virtually limitless, but I’ve always been drawn to a more fundamental value-based approach.

However, there are subtle differences within the value discipline itself and with how those principles apply to various investment types or methodologies.

Warren Buffett learned the basic investing methods from Benjamin Graham – but today, Graham would probably disagree with some of Buffett’s latest decisions.

Buffett’s approach has evolved over the years.

With several years of experience under my belt, I wanted to look back at my own evolution as an investor.

Dividend Increases = Income

A large portion of the historical return in equities is due to dividends, and this was one of the first places I looked when I started investing.

I paged through the Dividend Aristocrat and Champion lists, looking for companies that had regularly increased dividends, often for decades in a row.

There was something attractive about receiving that steady, quarterly deposit into my brokerage account, and then re-investing it back into more shares of the business.

As long as a dividend stock was purchased at a reasonable price, those dividend increases could provide a sizable return, especially over the long run.

However, I quickly realized that my investment goals did not match up to those of an income investor. While dividends are still core to my analysis, I no longer focus exclusively on them.

I am young and extremely driven.

I wanted to beat the market and was willing to take on more risk to get there.

(I made a living playing poker – market swings are tame by comparison!)

FCF is King

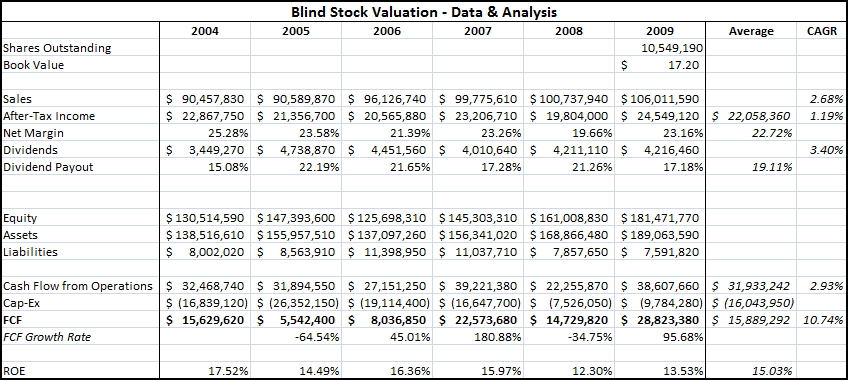

I quickly learned that analyzing the cash flow of the business is one of the most important indicators for long-term investing success. It is usually much better than the often-manipulated earnings numbers loved by the Street.

The best businesses – with the largest competitive moats – are able to grow FCF at a steady pace through the ups and downs of the business cycle.

These businesses are often large-cap stocks, having stocked up on brand reputation built to withstand minor fluctuations in the market.

When running stock screens, I looked for businesses that not only had positive FCF for the past 10 years, but were able to grow that cash flow every single year.

Then, by forecasting out future FCF increases and discounting back to the present, an investor tries to pick up shares at a discount to their intrinsic value.

Despite a solid method, finding quality businesses was difficult as many in this category (never having a down year) trade at a significant premium.

Sales are rare.

However, the financial meltdown in 2008-2009 touched even the most well-regarded businesses, and I managed to purchase many leading names at rock-bottom prices.

As the market rebounded, the discounts disappeared, and I continued searching for value in other market areas.

CROIC as a Key Metric

Largely influenced by the writings at FWallstreet (I cannot recommend Joe’s book and blog posts enough), I began to search for businesses with high CROIC. According to Joe, CROIC

“tells us how much cash our company can generate based on each dollar it invests into its operations.”

It is a great metric for evaluating companies, and it was possible to build a screen using Stockscreen123 to search for stocks with CROIC as the primary input.

Both ADVC and NOOF were found using the metric.

This number also became the basis for the growth rate in most DCF models.

OSV even provides a screen showing that businesses with improving CROIC substantially beat the market in the long run.

Over time, I kept running into the same companies over and over again, so it was time to look for opportunities using new methods.

Continued – Part II

Disclosure

Long NOOF, ADVC